China has announced that it will allow couples to have up to three children, after census data showed a steep decline in birth rates.

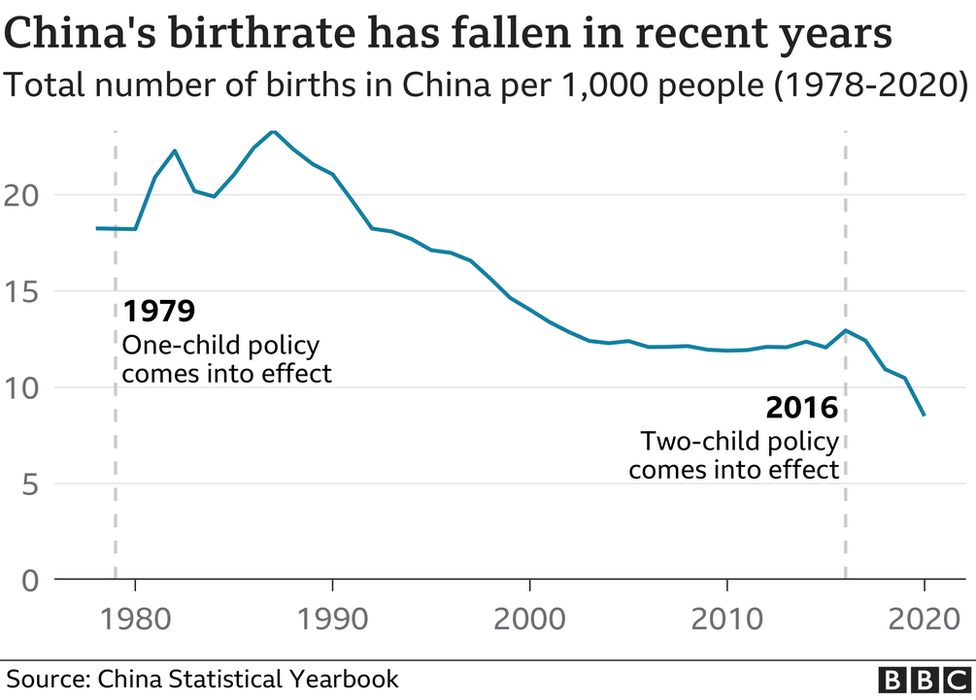

China scrapped its decades-old one-child policy in 2016, replacing it with a two-child limit which has failed to lead to a sustained upsurge in births.

The cost of raising children in cities has deterred many Chinese couples.

The latest move was approved by President Xi Jinping in a politburo meeting, state media said.

It will come with “supportive measures, which will be conducive to improving our country’s population structure, fulfilling the country’s strategy of actively coping with an ageing population and maintaining the advantage, endowment of human resources”, Xinhua said.

How are people reacting?

“If relaxing the birth policy was effective, the current two-child policy should have proven to be effective too, ” Hao Zhou, a senior economist at Commerzbank, told Reuters.

“But who wants to have three kids? Young people could have two kids at most. The fundamental issue is living costs are too high and life pressures are too huge.”

Zhiwei Zhang, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management, told the same agency that the immediate impact “is likely to be positive but small”.

“The long term impact depends on if the government can successfully reduce the cost for raising children – particularly education and housing,” the economist added.

On social media, some Chinese people also seemed less than excited about the new measures.

“[We can have] three kids, but the problem is I don’t even want to have one,” said one social media user on micro-blogging site Weibo.

“Do you know most young people already find it so exhausting to take care of themselves?”

One Beijing resident who spoke to the BBC ahead of the announcement echoed these thoughts, saying she wanted to “live my life” without the “constant worries” of raising a child.

What did the census say?

The census, released earlier this month, showed that around 12 million babies were born last year – a significant decrease from the 18 million in 2016, and the lowest number of births recorded since the 1960s.

The census was conducted in late 2020 where some seven million census takers had gone door-to-door to collect information from Chinese households.

Given the sheer number of people surveyed, it is considered the most comprehensive resource on China’s population, which is important for future planning.

It was widely expected after the census data results were released that China would relax its family policy rules.

What were China’s previous policies?

Even in 2016, when the government ended its controversial one-child policy and allowed couples to have two children, it failed to reverse the country’s falling birth rate despite a two-year increase immediately afterwards.

Ms Yue Su, principal economist from The Economist Intelligence Unit, said: “While the second-child policy had a positive impact on the birth rate, it proved short-term in nature.”

China’s population trends have over the years been largely shaped by the one-child policy, which was introduced in 1979 to slow population growth.

Families that violated the rules faced fines, loss of employment and sometimes forced abortions.

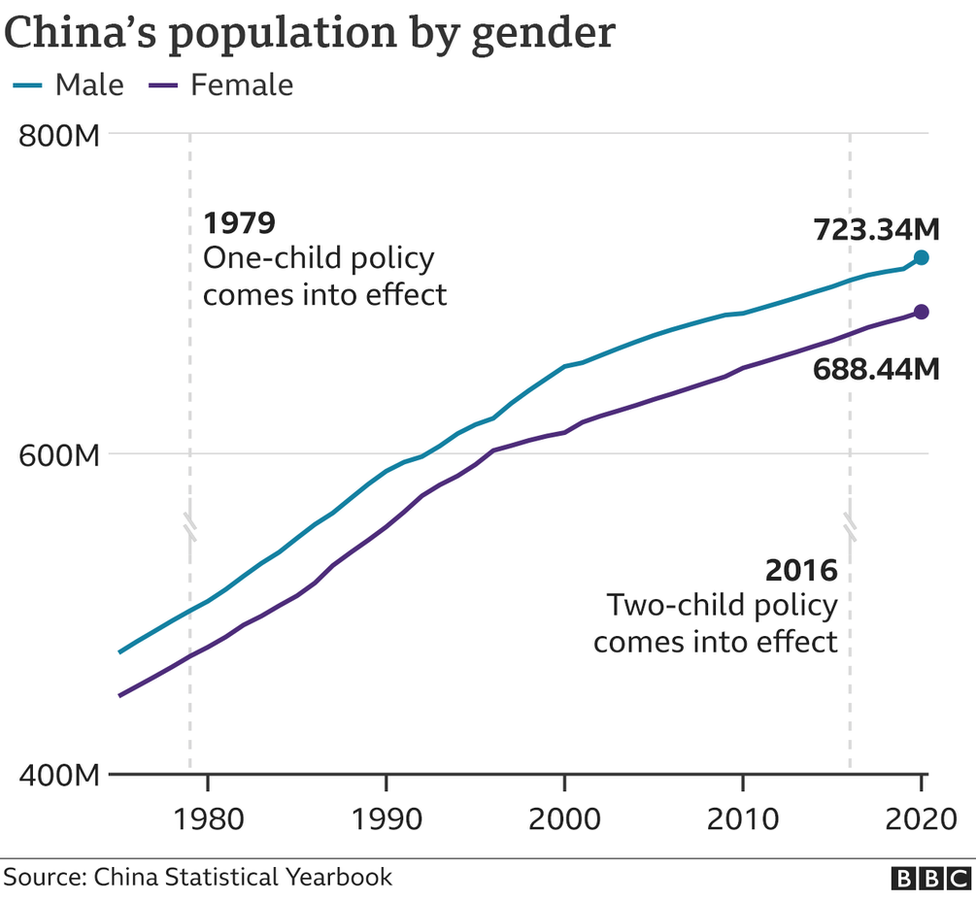

The one-child policy also led to a severe gender imbalance in the country – in a culture that historically favours boys over girls.

“This poses problems for the marriage market, especially for men with less socioeconomic resources,” Dr Mu Zheng, from the National University of Singapore’s sociology department, said.

Can China lift birth restrictions entirely?

Experts had ahead of China’s latest census, speculated that birth restrictions might be lifted entirely – though it appears as though China is treading cautiously.

But others had pointed out that such a move could potentially lead to “other problems” – pointing out the huge disparity between city dwellers and rural people.

As much as women living in expensive cities such as Beijing and Shanghai may wish to delay or avoid childbirth, those in the countryside are likely to still follow tradition and want large families, they say.

“If we free up policy, people in the countryside could be more willing to give birth than those in the cities, and there could be other problems,” a policy insider had earlier told Reuters, noting that it could lead to poverty and employment pressures among rural families.

Experts had earlier warned that any impact on China’s population, such as a decline, could have a vast effect on other parts of the world.

Dr Yi Fuxian, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said: “China’s economy has grown very quickly, and many industries in the world rely on China. The scope of the impact of a population decline would be very wide.”

SOURCE: BBC